The Brachial Plexus (From Roots to Cords), Nerves of the Neck & Related Injuries

- by Joanna Blair

- •

- 18 Oct, 2020

- •

Nerve Branches, Roots, Course and Innervation

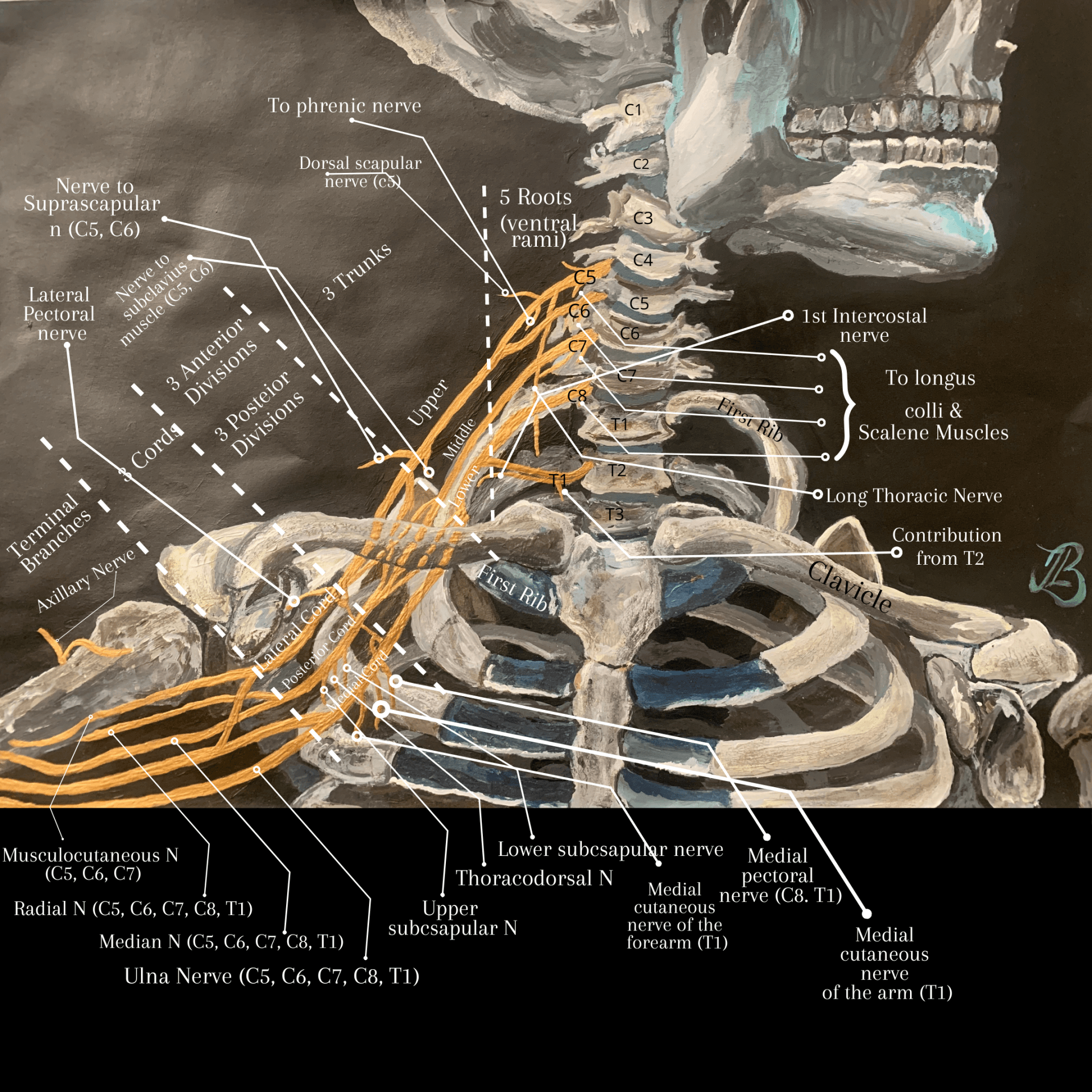

The Brachial Plexus (C5, C6, C7, C8 & T1)

Quite simply, the importance of our brachial plexus is such that without it, we would be unable to perform the various hundreds, upon thousands of simplest or complex movements which we automatically perform on a daily basis with our upper limbs. When studying and breaking down the brachial plexus into parts, it could be considered astonishing how this hidden delicate framework is so heavily relied upon for our upper limb movements, muscle strength and skin sensation.

Both 'brachial' and 'plexus' are Latin words, with 'Brachial' stemming from 'brachialis', meaning 'belonging to the arm'. The term 'plexus' means a network (i.e. blood vessels or nerves) or a structure containing a complex network of parts (1).

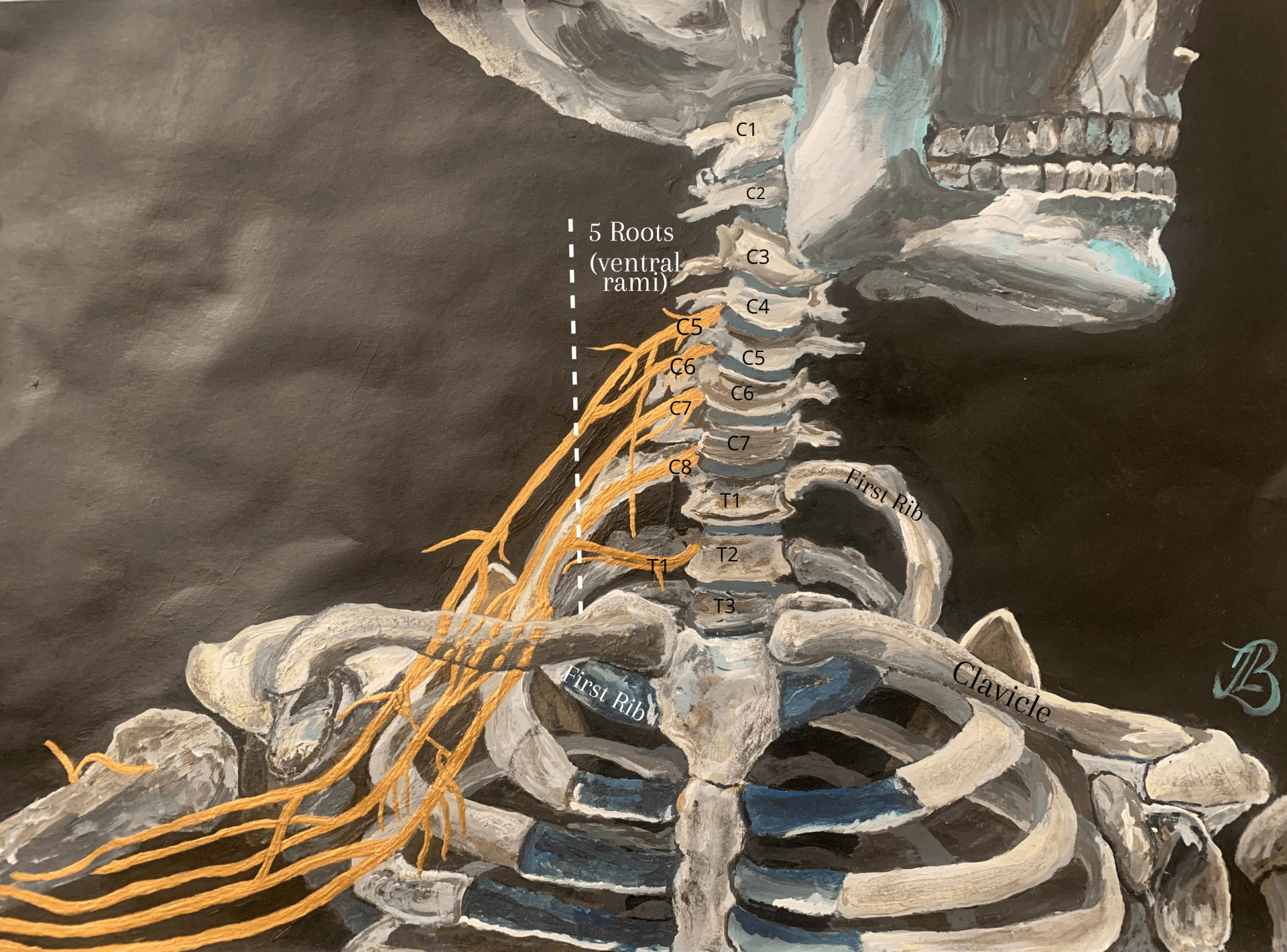

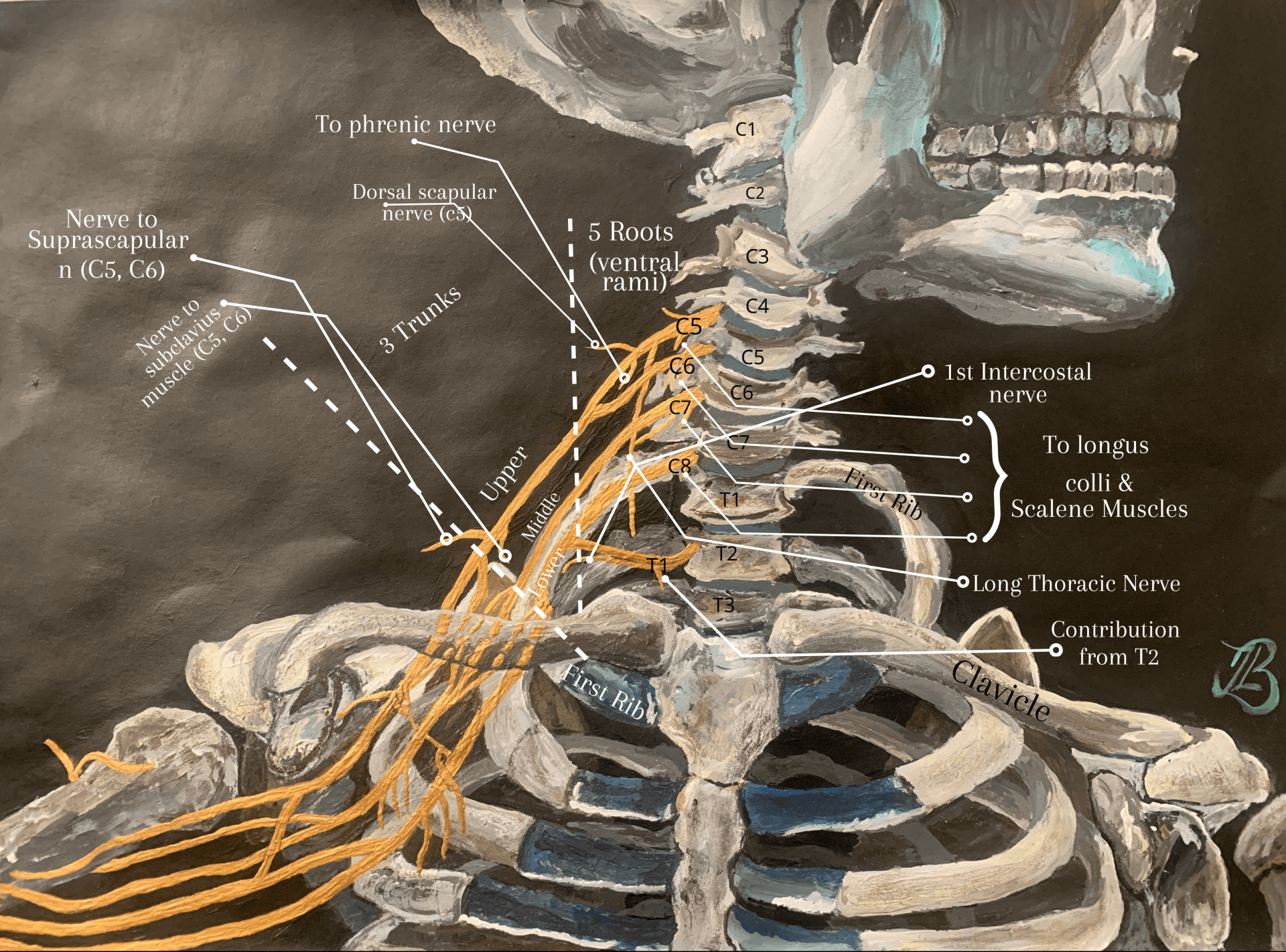

The plexus starts in the neck and is positioned between the neck muscles of the anterior and middle scalenes before passing through the axilla (or armpit) and descending down the arm to supply and innervate muscles, joints and skin of the whole arm and hand (11).

Knowing the brachial plexus and its neural branches is important for practitioners to know, as it can help determine whether a portion of the brachial plexus has been injured which can help tell us which of the associated muscles might be affected before being tested for evidence of a nerve injury (5).

Our 'Underground' Network of Nerves

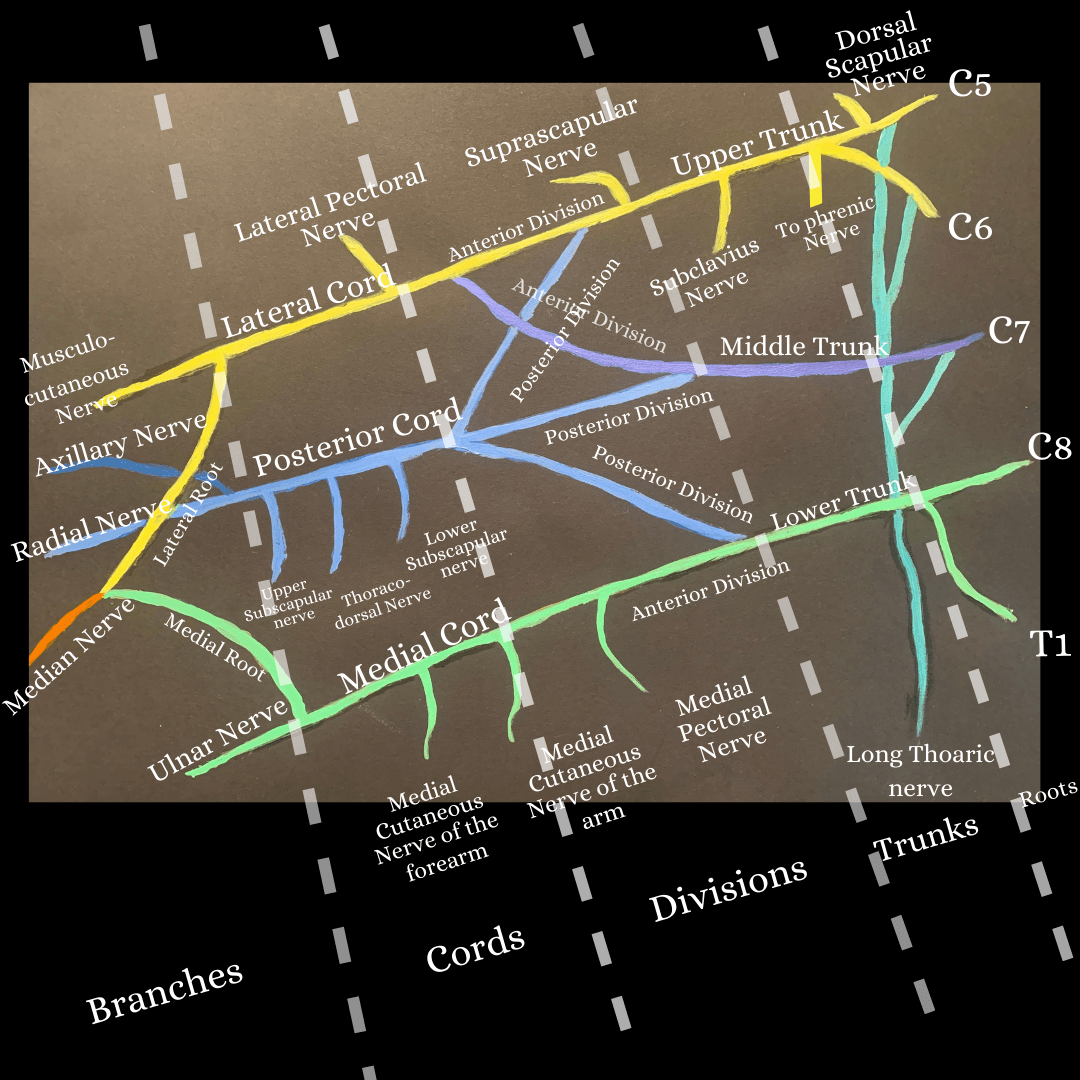

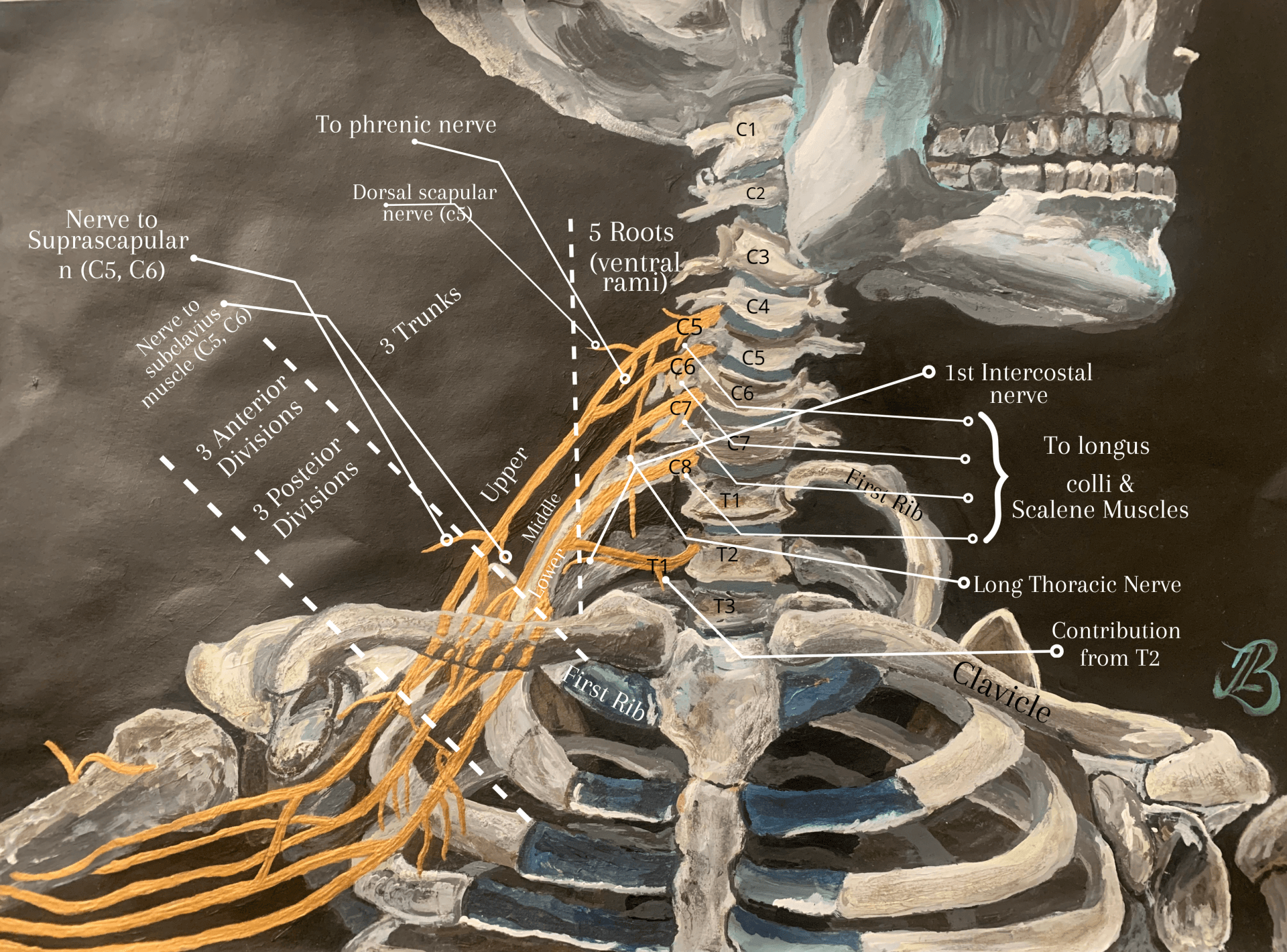

"Read That Deadly Cadaver Book"; Roots, Trunks, Cords & Branches

As the nerve roots exit the cervical and thoracicintervertebral foramen, or bony openings found between adjacent vertebrae, they unite and branch in the following order: roots, trunks, divisions, cords, terminal branches (and peripheral nerves) (11, 4). A helpful mnemonic for this is; Read That Deadly Cadaver Book (11). There is no difference in terms of function between each division and they are simply used as an aid to further explain or remember the brachial plexus (11).

The roots are the first section of the brachial plexus. Each spinal level has four nerve roots and there are two spinal nerve roots for the left and right side; the posterior (dorsal) and anterior (ventral) nerve roots. The anterior (ventral) nerve roots carry motor signals from the brain to the muscles and the posterior (dorsal) roots carry sensory signals from the skin to the brain (11). The anterior and posterior roots combine to form a spinal nerve at each intervertebral foramen (10).

The brachial plexus is formed by the anterior rami of cervical spinal nerves C5, C6, C7 and C8, and the first thoracic spinal nerve, T1. They unite in the neck between the anterior and middle scalene muscles, to form the trunks after the roots. The emergence of each root can be read below and followed from figure 1 and figure 2:

1st root: arises from the anterior ramus of C5 above the 5th cervical vertebra (Figure 3.).

2nd root: Arises from the anterior ramus of C6 below C5.

3rd root: From the anterior ramus of C7 below C6.

4th root: From the anterior ramus of C8 emerges above the first thoracic vertebra.

5th root: Arises from the anterior ramus of T1 emerges below the first thoracic vertebra (4).

The three trunks of the brachial plexus originate from the roots and are located within the lower part of the posterior cervical triangle and pass laterally over the first rib before entering the axilla (2, 4) Figure 4).

The Upper (superior) Trunk: The first of the three trunks is the upper (superior) trunk and is formed by the union of the anterior rami of C5 and C6. Two nerves arise from the superior trunk which are the subclavian nerve and the suprascapular nerve.

The Middle Trunk: The second trunk or the middle trunk originates directly from the anterior ramus of C7.

The Lower (inferior) Trunk: is composed of two nerves via the anterior rami of C8 and T1.

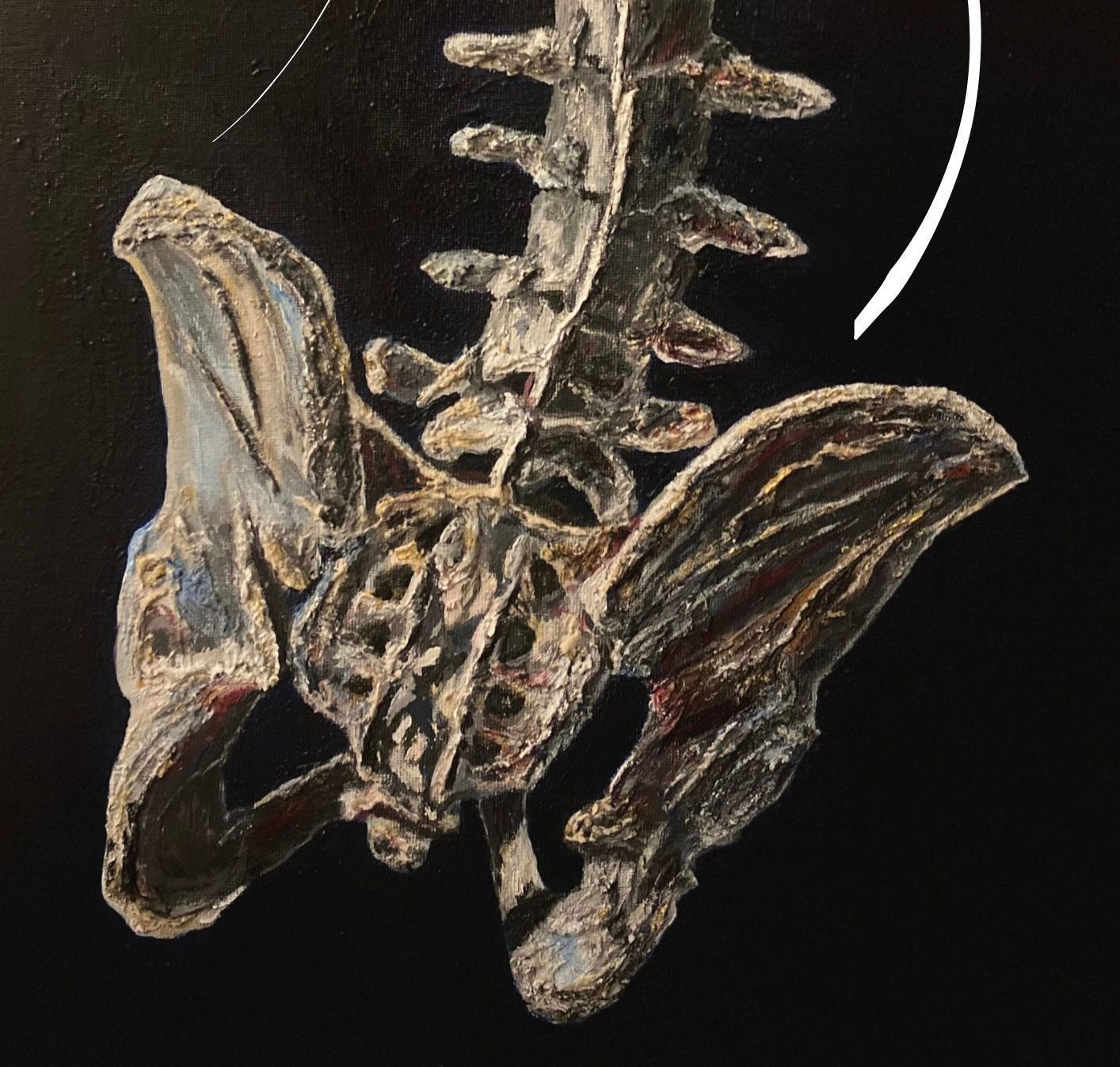

Each trunk then divides into anterior and posterior divisions which pass beneath the clavicle where there are no nerve branches at this level as can be seen from my labelled painting below in figure 5 where the dotted golden lines represent the divisions that pass beneath the clavicle (5).

The Divisions

Overall, there are six divisions situated beneath the clavicle comprising of an anterior and posterior division from each of the three trunks with three anterior division fibres supplying flexor muscles and ultimately give rise to nerves associated with the anterior compartments of the upper limb (4). The posterior division fibres tend to supply extensor muscles and give rise to nerves associated with the posterior compartments of the upper limb (4).

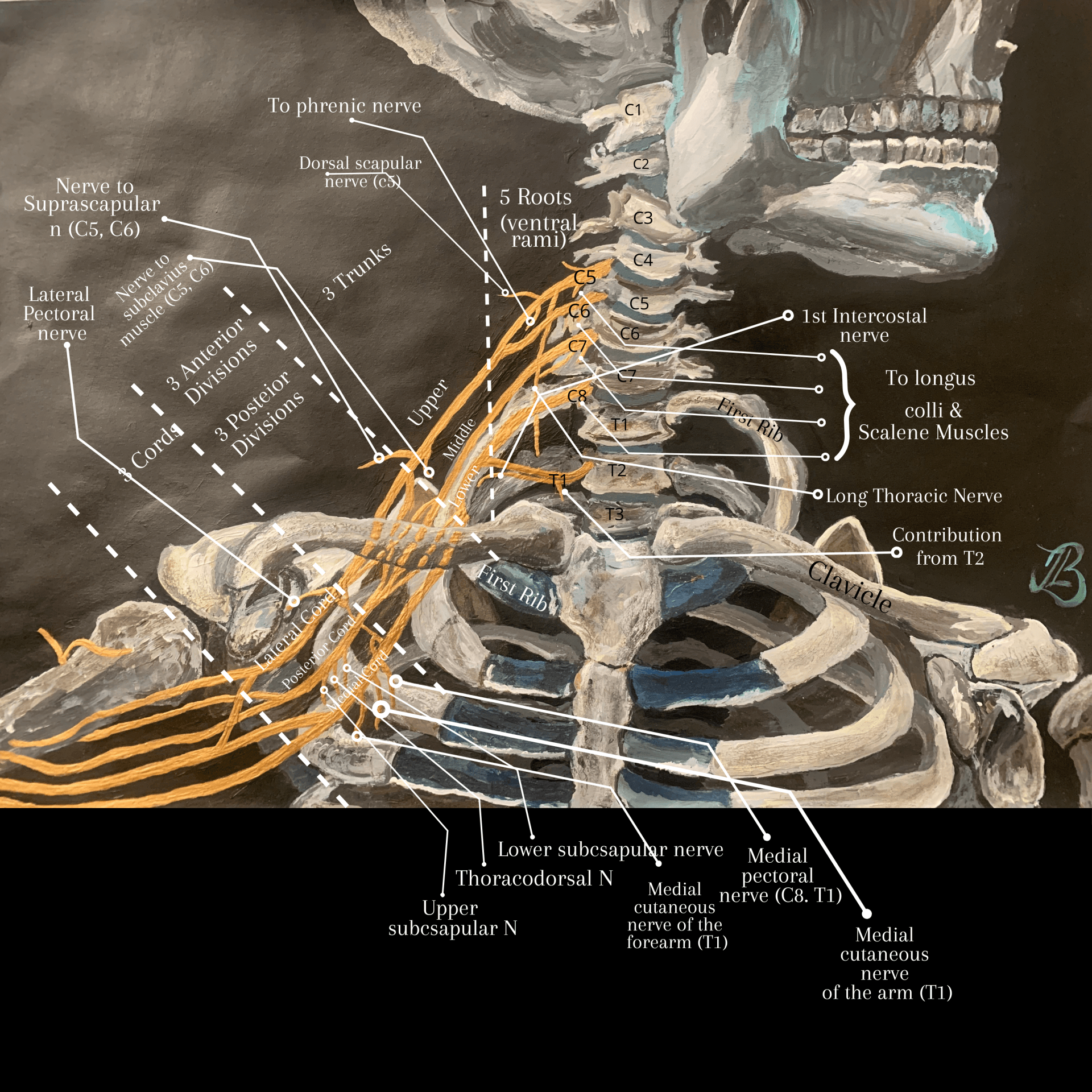

The cords are the fourth section of the brachial plexus, are named based on their positioning with respect to the axillary artery found distally to the clavicle and at this level are termed 'the infraclavicular brachial plexus ' (5) (Figure 6). The cords, axillary artery and vein are located deep to the pectoralis minor and major muscles in the infraclavicular fossa and is a target site for anaesthesia of the upper limb and for brachial plexus nerve blocks (3).

The cords are formed as follows:

The Lateral Cord (on top):

The lateral cord gives gives a branch to the lateral root (or 'head') of the median nerve and gives rise to the lateral pectoral nerve before it continues into the upper limb as the musculocutaneous nerve (figure 1 and 2).

The distal branch of the lateral cord, the lateral pectoral nerve, innervates the clavicular head of the pectoralis major and weakness indicates lateral cord injury (5).

The Posterior Cord (in the middle):

The posterior divisions of all three trunks unite to form the posterior cord which means that they receive input from all levels of the brachial plexus (C5 to TI). The posterior cord gives rise to three branches before it terminates as the axillary nerve and the radial nerve; namely, the upper subscapular nerve, the thoracodorsal nerve and the lower subscapular nerve (figure 2 (and 3)).

The Medial Cord (at the bottom):

The medial cord is the continuation of the anterior division of the inferior trunk, and like the posterior cord, it gives off three branches before it terminates as the ulnar nerve. These branches are the medial pectoral nerve, the cutaneous nerve of the arm, and the cutaneous nerve of the forearm (figure 1 and 2).

Injuries:

Medial Cord Injury:

The union of the two anterior divisions of the superior (or upper) and middle trunks form the medial cord. The medial cord gives a branch; the medial root (or named ' medial head' in some texts) of the median nerve and continues as the ulnar nerve (Figure 2) (3).

Injury to Medial and Lateral Cords and How it May Affect the Pectoralis Major Muscle:

The medial pectoral nerve that arises from the medial cord and with the branches from the lateral pectoral nerve from the lateral cord innervate the sternocostal head of the pectoralis major muscle (4). Examination of the pectoral major muscle is necessary to localize a cord level injury as pectoralis major clavicular head (which creates humeral flexion) involvement implies lateral pectoral nerve injury and sternocostal head (which adducts the humerus) involvement of the pectoralis major implies injury to both the lateral and medial pectoralis nerves, i.e. both medial and lateral cords (4).

The Brachial Plexus Nerve Branches (From Rami to Cords) and Muscular Supply

Phrenic nerve ( Rami C3 to C5): Diaphragm (keeps the diaphragm alive)

Dorsal Scapular Nerve (C5 Rami): rhomboid minor and rhomboid major, Levator scapulae

Long thoracic nerve (C5, C6 & C7 Rami): Serratus Anterior

Suprascapular nerve (C5 & C6 upper trunk): Supraspinatus & infraspinatus

Nerve to subclavius (C5 & C6 upper trunk): Subclavius muscle (clavicle stabiliser)

Lateral pectoral nerve (lateral cords): Sternocostal head of the pectoralis major muscle (5)

Upper subscapular nerve (Posterior cord C5, C6): Superior portion of the Subscapularis

Thoracodorsal Nerve (Posterior Cord: C5, C6, C7 and C8): Latissimus Dorsi

Lower subscapular nerve (Posterior Cord; C5 and C6): Inferior portion of the subscapularis and the teres major.

Medial Pectoral Nerve (Medial cord; C8 & T1): pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles.

Medial Cutaneous Nerve of the arm (Medial cord; C8 & T1): [smallest branch of the Brachial Plexus] Supplies the skin on the medial brachial side of the arm

Medial Cutaneous Nerve of the Forearm (Medial cord; C8 & T1): supplies the anterior and medial aspects of the forearm and the distal wrist.

Upper Brachial Plexus Injury; Erb-Duchenne Palsy

Typically, the presentation of an affected limb is to hang limply and be held in adduction with internal rotation at the shoulder jointfrom the unopposed action of the pectoralis major muscle (12). At the elbow joint, there is extension and pronation caused by atrophic muscle changes within biceps brachii and spasticity of the wrist flexors along with flexion of the fingers (11). This overall presentation has contributed towards the term "waiter's tip deformity". The typical symptom is numbness (anaesthesia) along the lateral aspect of the arm.

The most commonly involved nerves include suprascapular nerve, musculocutaneous nerve, axillary nerve and nerve to subclavius. The muscles that are affected include deltoid, supraspinatus, teres minor, subclavius, infraspinatus, biceps, supinator, coracobrachialis, and brachioradialis muscles of the upper limb (12).

From an incident post birth, the neurological examination is characterized by the absence of Moro’s, biceps, and triceps reflexes of the affected upper limb with the presence of grasp reflexes as interossei muscles are not affected (9). Sometimes diaphragmatic paralysis is also seen if associated paralysis involves C3 and C4. At this age, treatment involves conservative management with performing physiotherapy and exercises to prevent muscle contracture which starts 7-10 days post injury and overall has excellent prognosis with good neurological outcome (10).

Lower Brachial Plexus Injury: Klumpke Palsy

The injury is usually caused via traction on an abducted arm in circumstances from e.g. an infant being pulled from the birth canal by an extended arm above the head or with someone catching themselves by a branch as they fall from a tree (12).Another cause could be from a compression injury and cause similar signs and symptoms via an apex lung tumor which may press on the cervical sympathetic ganglia of C8 to T1 nerve roots and sympathetic involvement can cause a Horner's syndrome presentation (8).

The classic presentation of Klumpke's palsy is the “claw hand”, as all the intrinsic muscles of the hand are affected with a supinated forearm, the wrist becomes extended with the fingers flexed. If Horner syndrome is present, there is miosis (constriction of the pupils) in the affected eye (12). Thus, the ulnar and medain nerves are affected and a loss of sensation along the medial side of the arm is usually reported (11).

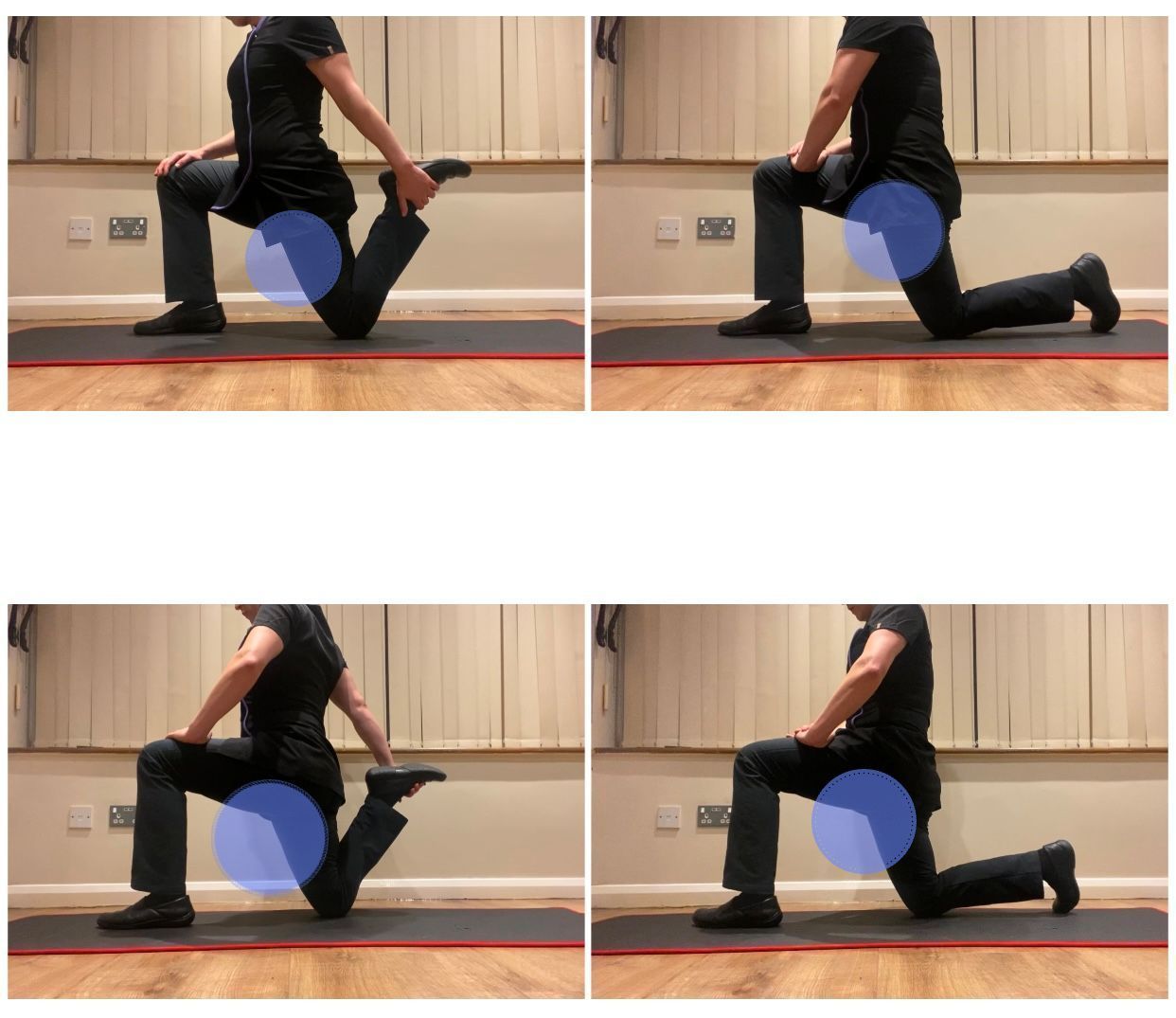

For an open related injury i.e. there is an open fracture,obvious break through the skinor severe vascular compromise, emergency surgery in this instance would required. For closed injuries, conservative treatment via physiotherapy may includes strengthening and stretching exercises the supportive and affected surrounding muscles to help maintain the range of motion and aid a full recovery (8).

If there is no improvement post 3 to 6 months of injury, surgery would be a requirement which would involve nerve grafting. In cases of injuries proximal to the dorsal root ganglion, neurotization or nerve transfer is most recommended which can be defined as 'the transfer of a healthy but less valuable nerve or its proximal stump reinnervating a more important sensory or motor territory that has lost its innervation through irreparable damage to its nerve' (7). Merryman and Varacallo (2018) note that in most cases, the nerves will eventually heal and spontaneous recovery from nerve palsy is possible, but most C8-T1 nerve palsies do not recover without intervention.

References

2. Kattan, A. E., Gregory H. Borschel, G. H. (2011)Anatomy of the Brachial Plexus, Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine: An Interdisciplinary Approach; 4: 107-111.

3. Keet, L., Louw, G. (2018) Superficial location of the brachial plexus and axillary artery in relation to pectoralis minor: a case report, Southern African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia; 24(4):114–117.

4. Kenhub (2020) https://www.kenhub.com/en/study/the-brachial-plexus [online] last viewed 18/10/2020.

5. Kim, D. H., Murovic, J. A., Kline, D. G. (2004) Brachial Plexus Injury : Mechanisms, Surgical Treatment and Outcomes,

https://www.jkns.or.kr/upload/pdf/0042004153.pdf [online]last viewed 11/10/2020.

6. D’amore, A., Conte, G., Viglianesi, A., Chiaramonte, R., PERO, G. Chiaramonte. (2010) Evaluation of a Patient with Klumpke’s Palsy A Case Report, The Neuroradiology Journal; 23: 325-328.

7. Narakas, A. O., Hentz, V. R. (1988) Neurotization in Brachial Plexus Injuries Indication and Results, Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research; 237: 43-56.

8. Merryman, J., Varacallo, M. (2018) Klumpke Palsy, StatPearls, NCBI Bookshelf: 1-4.

9. Patil, D. Y. (2016) Duchenne-Erb’s palsy in newborn: Result of birth trauma, Medical Journal of Dr. D.Y. Patil University, 9; 2: 274-276.

10. Snell, R. S. (2007) Clinical Anatomy By Systems, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

11. Teach Me Anatomy; The Brachial Plexus, plexushttps://teachmeanatomy.info/upper-limb/nerves/brachial-plexus/[Online] Last visited 13/10/2020.

12. Wikipedia, Klumpke Paralysis, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klumpke_paralysis, [online]last viewed 18/10/2020.